by Dave Umbricht

Sex, politics, religion, and Michael Moore.

Four things one should never bring up in a job interview or a polite dinner party. A few years ago, one’s views on Moore’s films said something about political leanings. Think Farenheit 9/11 was hard hitting journalism? You must be a commie pinko. Enjoyed Bowling for Columbine? Then you don’t believe in a little something called the Constitution and our right to bear arms. Moore’s crusades tend to bring more controversy than actual good these days, and sometimes it feels he is either late to the party or too flippant with his topics.

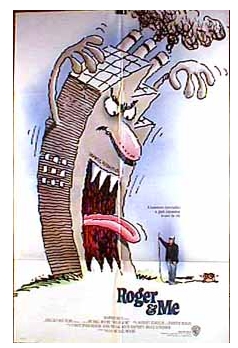

That should not take away from the fact that once upon a time Moore actually made a great film. His 1989 debut, Roger & Me, is entertaining, influential, and most of all, an insightful documentary.

Michael Moore was born and raised in Flint, Michigan, birthplace of General Motors. For 50 plus years, Flint defined itself by its connection to the auto industry, until GM started closing the plants. In Roger & Me, Moore chronicles the effects that plant closures have on the residents of Flint, interviewing people from all areas of the community.

Because it took Moore a number of years to make the film, the audience witnesses the slow decline of Flint, watching shopkeepers shutter stores and ordinary citizens lose their homes. He delves into many sides of the story, seeing the reactions of union leaders, line workers, and even post office employees deluged by an influx of change of address requests.

Moore intercuts his tour of Flint with his attempts to gain a meeting with the Chairman of General Motors, Roger Smith. This is the gimmick that Moore has become famous for over the past 20 years, bullying his way into corporate headquarters to ask the bosses pointed questions. In this case, he wants to know why General Motors, at the time one of the most profitable companies in the world, could close plants and move Flint’s jobs to Mexico.

Moore intercuts his tour of Flint with his attempts to gain a meeting with the Chairman of General Motors, Roger Smith. This is the gimmick that Moore has become famous for over the past 20 years, bullying his way into corporate headquarters to ask the bosses pointed questions. In this case, he wants to know why General Motors, at the time one of the most profitable companies in the world, could close plants and move Flint’s jobs to Mexico.

While Moore’s notoriety makes his CEO stalking impossible today, it was incredibly effective then, as his relative anonymity allowed him more time on the premises before being escorted off by security. Making himself a character in the documentary was ahead of its time. Without Moore, we may not have had a Morgan Spurlock, or even a Borat. Critics of Moore point to his involvement as a weakness, but Roger & Me is both a biography of Flint and the closest thing to an autobiography of Moore that we have.

Moore has always been a controversial figure. After the release of Roger & Me, there were complaints that not all of his facts were straight, including the chronology and magnitude of some events. This is a charge that has plagued him more so in recent times, as he has bitten off more complex and politically charged topics, such as the healthcare system in Sicko.

And while Roger & Me was critically acclaimed, it failed to receive an Oscar nomination for best documentary. However, some of the controversy surrounding that incident said more about the documentary nomination process than the movie itself.

Moore has lost a lot of his influence since the release of Roger & Me. It was inevitable, as once he became well known, he could not swoop in on unsuspecting CEOs and government officials. In his latest film, Capitalism: A Love Story, as Moore confronts a congressman on a cell phone, the congressman tells his wife, “Michael Moore, the filmmaker is here.”

That hardly sets the stage for unguarded comments.

Moore has also taken on more complex subjects: gun control, 9/11, healthcare, widespread financial crisis. Trying to tackle something so deep in two hours or less will lead to many sections only scratching the surface, and in some scenes, the audience only receives a one-liner like, “Isn’t this a bad situation?”

In Roger & Me, he took his time, getting to know people throughout the film. For example, the audience spends a lot of time with Fred, the sheriff’s deputy, charged with foreclosing homes. We see him evict people he knows, even on Christmas Eve. We see his conflict and we see the distress of those being evicted. In Capitalism, we see the evictor portrayed as a stooge of the bank, the people losing their homes as saintly and no discussion of the facts surrounding the foreclosure. In Roger & Me, he shows the human toll that these situations take, in Capitalism it feels like heavy-handed propaganda.

There is a lot of anger in Moore’s films. But can they convince people to change the world? What does it take to move people from indignation to rallying in the streets of Cairo demanding a regime change? While the complete answer to that question is quite complex, and requires a lot of organization, the simple answer is Michael Moore can never do it.

It is not entirely his fault. It is the limitation of film as a medium. Movies entertain and sometimes inform, but most of all they make us feel. But feelings are fleeting, and any anger or resolve that the audience may walk out with after two hours will dissipate over coffee. These fires must be stoked, and the logistics of watching movies does not allow for that.

You cannot easily pull out your favorite scene from the movie to show to your friends over lunch. You cannot look at it one more time right before you go to bed, without some serious effort. Books can be taken out any time, they allow time for thoughts to gestate and are easy to revisit. That is why the printed word will always trump a film as the most rallying form of media. Moore may be insightful at times, but he will never be as inciteful as he hopes.

In the end, controversy and lasting impact do not matter. Michael Moore made an exceptionally affecting film with Roger & Me. It is a human story, one everyone should be able to connect with, no matter your politics or economic beliefs. The mark of a great documentary is showing a small, focused story that speaks to a more universal truth.

Roger & Me tells of the decimation of Flint, but it also speaks to the larger issue of a changing industrial and manufacturing landscape that affected America for the next twenty years. It even foreshadows Moore’s later work, as the events in Flint are some of the seeds that led to the events that Moore rails against in Capitalism.

Yes, Michael Moore may have become less effective over the years and has ended up being just a big blowhard, but in Roger & Me, he started as an entertaining one.

Dave Umbricht loves his family, movies and the NBA (in that order). His unexplainable, genetic attraction to movies flourished in the early ’80s thanks to Siskel and Ebert. It’s also believed Dave was the only 8-year-old to know of My Dinner with Andre, even though he didn’t see it until he was 28. In the ’90s he wrote three awful screenplays, including next summer’s Cowboys and Aliens (or at least a script with the same title). He still can’t dunk a basketball.