by Dave Umbricht

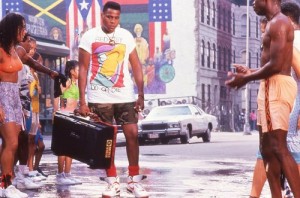

In 1989, the media billed Do the Right Thing as a dangerous movie, suggesting lives were at risk if viewed in a theater. The panic was overblown, but the movie remains incendiary. From the opening moment when Rosie Perez explodes onto the screen, shadow boxing to the pulsing beats of Public Enemy, few films energize the audience and take them through an experience that captures the highs and lows of being human.

In 1989, the media billed Do the Right Thing as a dangerous movie, suggesting lives were at risk if viewed in a theater. The panic was overblown, but the movie remains incendiary. From the opening moment when Rosie Perez explodes onto the screen, shadow boxing to the pulsing beats of Public Enemy, few films energize the audience and take them through an experience that captures the highs and lows of being human.

Spike Lee had garnered the attention of critics a few years earlier with his films She’s Gotta Have It, a slight romantic comedy/drama and School Daze, a depiction of life at a small black college. Most Americans never saw those movies, but they knew Spike from the Nike commercials that paired his She’s Gotta Have It character, Mars Blackmon, with Michael Jordan. This popular culture notoriety marked Spike as an important auteur before he crafted a film to match that acclaim. Then he made Do the Right Thing.

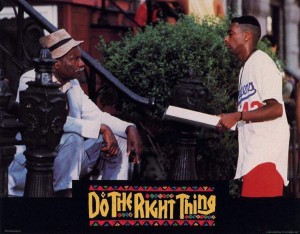

The movie spans a hot summer day. Too hot. All the residents of Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood want to do is make it through the day and stay cool. The film follows Spike Lee’s Mookie as he delivers pizzas through the neighborhood. But Mookie is not the real main character, the neighborhood is. Every resident receives attention, from

Mother Sister, the old matron who sits on her stoop supervising everyone’s actions to Da’ Mayor, the old wino who needs his Miller High Life to escape a life of disappointment and unfortunate decisions. Each character builds the mosaic of life on the block, highlighting the tenuous racial acceptance of each other, and the small interconnected acts that can undermine it.

Spike Lee started with the very weighty subject of race relations and then used every tool in his director’s kit to create a stylistically memorable movie. The brightly colored set designs, the way the sun seems to reflect off of the character’s sweaty skin, and the skewed framing of some shots give an otherworldly feeling. Everything about the style pulses with life, especially the music. One of the themes in the movie contrasts the teachings of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. While there are overt references to the two, the score is an auditory reminder, alternating between a soothing jazz score (the loving response of MLK) and the powerful, attacking rhythms of Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (the action oriented response of Malcolm X).

Revisiting the movie twenty plus years later, I was surprised how my perception of it was so different from reality. I remembered the danger, thinking the movie gave me a glimpse of a world I would never visit lest I risked my life. However, the neighborhood depicted is populated by everyday working citizens. There are no drug dealers and no thugs. The only gang on hand dons pastel colors and includes Martin Lawrence as a member, hardly frightening. The real menace to the neighborhood is the mistrust and fear of one another. And we watch as the reactions to this universal human trait slowly builds to a troubling climax. There is a great deal of debate about the ending section. It is not perfect, but neither is life, which makes this film even more life affirming.

Spike Lee is a polarizing filmmaker. Unlike some, he does not have blind allegiance from film fans. His movies are judged on their individual merit. Some of his later work has been very good, such as 25th Hour, and some has been excruciatingly preachy, like He’s Got Game. In the ’80s, Spike was a lot like the guy with whom he shared the Nike commercial, both had a ton of potential. Spike reached his pinnacle in 1989, a few years earlier than Jordan. He may have never reached the same heights as he did with Do the Right Thing, but that does not matter, it is one of the most kinetic movies out there, and it never fails to energize.

Clip from Do The Right Thing (1989)

Dave Umbricht loves his family, movies and the NBA (in that order). His unexplainable, genetic attraction to movies flourished in the early ’80s thanks to Siskel and Ebert. It’s also believed Dave was the only 8-year-old to know of My Dinner with Andre, even though he didn’t see it until he was 28. In the ’90s he wrote three awful screenplays, including next summer’s Cowboys and Aliens (or at least a script with the same title). He still can’t dunk a basketball.